Web Views Are Green Screen

Dec 19, 2012

That's the set of Lord of the Rings, taken around twelve years ago. Even a decade later, these films have hardly aged a day, mainly due to what is evident from this photo: beautifully designed set pieces. The relatively early computer graphics of the time are (with the exception of Gollum) rarely front-and-center, as the production opted for a real-life, intricately crafted world using as little green screen as possible.

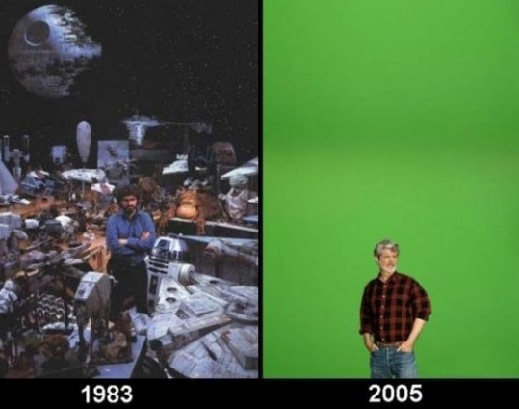

And a decade later, you just don't find this kind of movie set anymore. Instead, we get last two Star Wars prequels, filmed in giant green and blue boxes.

In moderation, green screen works wonderfully, drawing us further into the film's world and breathing life into the impossible; at its worst, digital meddling is jarring and actually takes us out of the experience, making us wonder, "Oh yeah, that's not real." And then we're no longer thinking about the characters or the story: we're thinking about the fact that this is a movie, and those are computer graphics.

The same holds true for the web views we often embed in mobile apps: executed when necessary and with great skill, they can actually create a better user experience. But when we fudge them up, as we often do in these nascent days of mobile development, it breaks the illusion and users are left thinking, "Hmm, why doesn't this bit work like everything else?" And then our users aren't thinking about their original purpose of opening the app: they're considering the technology and pondering why it doesn't feel quite right.

George Lucas and many other filmmakers embraced the digital, green-screen-everything revolution in part because it meant a less cumbersome and more flexible process: no rolls of film to worry about, and if you're not sure how to design a set right now then it can all be changed in post-production. Sound familiar? Sort of like, "No Objective-C or Java to compile! We can change at any time from the server!"

The temptation with web views is our ability to change things without an additional app approval cycle, and that ability can be a practical requirement or strategic advantage. But it comes at the risk of making that part of the product feel unnatural, especially given how precisely a web view needs to be programmed to make it look-and-feel native. And the more upfront your app is with its web views, the more obvious it will probably become. Just like bad green screen effects.

Those are the risks...but there is also another way. Pixar films are entirely computer-generated, which means nothing looks out-of-place and our brains aren't busy thinking, "This part is real but that bit over there is fake." This is why WebOS was so promising: its third-party apps felt natural because, despite being just HTML and CSS, everything else the user interacted with on the device was also a just web page! There wasn't a destination between "web" and "native": it was all the same.

Maybe that's why it's such a tragedy that WebOS didn't take off, or that Google has pushed Android onto millions of devices instead of a mobile version of Chrome OS. For one reason or another, web-browser operating systems just haven't taken off, and that means native software will continue to be a better solution when forming the ideal user experience. Just like hand-crafting films will yield more timeless results than giant green boxes.

At the end of the day, after the lights turn off and the actors have left, all the special effects in the world won't prevent you from making a bad movie. Whether we're producing motion pictures or mobile apps, we're telling stories, trying to create something people care about with nothing but our minds and our hands. And if our core idea just doesn't work, then no amount of digital sugar-coating will save it.